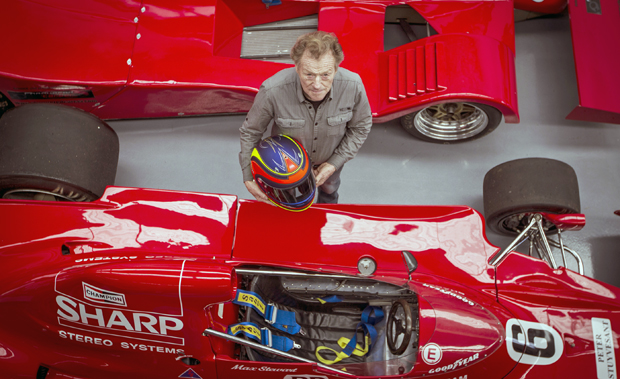

Kenny Smith has a collection of memorabilia upstairs in his garage at Hampton Downs.

On one wall are scores of trophies he’s won over the years and scattered around are images of races from yesteryear, framed certificates, old racing helmets, sashes, wreaths and books. It takes up the entire floor yet is only a fraction of all the memorabilia he possesses.

It’s hardly surprising, considering Smith is entering his 57th consecutive season on the motor racing circuit. The 73-year-old first raced competitively in 1958, when he claimed the New Zealand Hill Climb Championships as a 17-yearold, and has barely stopped winning since.

He’s accumulated three New Zealand Grand Prix titles (1976, 1990and2004), five Gold Star driver awards, three Formula 5000 titles, three Penang Grand Prix titles, won the Selangor Grand Prix twice and the Malaysian Grand Prix. And he’s also been awarded anMBE.

Even his most recent start, last weekend’s Formula Atlantic racing at Hampton Downs, he won.

“I hang in there,” he says with a grin. “I don’t think I’ve got any slower. I love it. January will be the 57th year I’ve done it without missing a season. It might be a world record. It would be close to it. A lot of people get into it later in life but not many do it continuously.

“My reaction time is as good as it’s ever been. It hasn’t gone away. I’m as sharp as anyone when it comes to the lights on a grid. A lot of the driving is done with your head. You work out how you’re going to psyche out the guy who’s beside you or in front and work him over. It’s not just driving a car.”

Smith’s chassis has a few dents on it and he looks his age. He has deep set wrinkles etched into his face like widening cracks on a road and arthritis in his hands. He’s also had a triple bypass and has had a few stents inserted in his arteries.

He once even completed a race with his heart medication taped to the dash board.

“The most amazing thing is he looks only 70 because I’m sure he’s 150,” jokes Bob McMurray, who was involved with Formula 1 team McLaren for 30 years and became a voice of motorsport in New Zealand.

Appearances can be deceiving. Smith still has the wavy hair that seems to spring back after being constrained under a racing helmet and he bounds up the stairs to find an old photograph like a teenager.

He must undergo a medical each year before he’s allowed to race but says “it’s no problem passing it”.

“My cardiologist says my fitness rate on a 12-minute treadmill test is better than most 40 year olds. I don’t go to a gym – fitness helps, of course, but a lot of people go overboard on fitness and probably do more harm wrecking themselves – but I’m on the move all the time, lugging engine boxes around. That keeps your mind and body sharp.”

He’s put on weight since his prime racing condition, although that’s relative. He used to pack 57kg-58kg around his diminutive 1.57m frame but is now a hefty 64kg.

He still slips easily into the single-seater cars he’s been racing for most of his life.

It’s a good life and one he’s not about to give up.

“As long as I can see and get in a car and feel that I haven’t lost the edge, I will keep going,” he says. “If you want to sit at home and watch TV all day, you will sit there and die.”

There was a period in the late 1980swhen it seemed the chequered flag was being waved on his career. He had just had a triple bypass heart operation and a cardiologist told him to stop racing.

“That was a big shock,” he admits. “It knocks you back when someone says that. I suppose that’s typical of what they have to say when they think you are in bad shape but they don’t realise that it’s not the end of life. You keep going. I was lucky. Twenty years prior to that [operation], you would have been dead with those sort of complaints.

“I contemplated the end for a couple of weeks but then I thought this was bullshit. Once I had the bypass done and was on my feet, I worked hard on getting fit. Two months later, I was back in the car and did the whole series. I had a hell of a year doing it.”

Smith finished second behind Paul Radisich in the New Zealand Grand Prix, an agonising result for a couple of reasons. Not only did he miss another title by one-tenth of a second but he also suffered in the car.

His back ached painfully every time he went over a bump on the Pukekohe track and he contemplated retiring but was still mixing it with Radisich so attempted to get more comfortable.

“I loosened the seat belts and turned my body sideways and used my shoulder to hold myself up,” he says. “My foot was on the steering rack which runs through the car and I jammed myself stiff in there. The next day, I found out that when they do a bypass, they pull you open and crack some bones and one of them was piercing a muscle in my back and bleeding in there.

“I got it looked at and they said, ‘you’ll have to stop now, you won’t be able to carry on for the rest of the season’. I said, ‘OK’. Next weekend, I was back racing at Manfeild.”

Racing used to be a family affair for the Smiths. Father Morrie introduced a young Kenny to cars and it wasn’t long before he was “laying some rubber” at the lights on the streets of Point England.

“Some of the cars I raced, I used to test them on the streets, upsetting the neighbours,” he says. “That didn’t matter.”

Kenny and his father painted cars before the pair worked together in a car yard. Morrie also acted as chief mechanic until he died in 1988 and the rest of the family tagged along to watch.

“My mum went to every race meeting I went to until five years ago when she died,” Smith says.

These days, the motor racing fraternity is his family.

“I’m not married,” he says. “How can you be married and go motor racing? I have seen so many of my friends married and so many broken marriages over motorsport.”

But Smith has ‘adopted’ plenty of youngsters in his time. Just as significant as his success as a driver has been his ability to spot and nurture young talent and get them started.

Scott Dixon, Brendon Hartley, Shane Van Gisbergen, Daniel Gaunt, Greg Murphy … they’ve all had help from Smith.

“When I was really young, Kenny was a bit of a mentor and helped a lot, just as he’s helped a lot of guys over the years,” says Dixon, the former Indy 500 winner and three-time IndyCar Series champion.

“For me, during the end of my time in New Zealand, it was his contacts that were really important. He just know things after racing for so long. The one guy you’d want to pick the brains of would be Kenny.

“He loves being involved and helping. He just plain loves racing, man. That’s the cool part of it. He’s really enjoyed seeing the success of all the guys he’s helped and, whenever I get back [to New Zealand], I always try to set a day aside to go and see him and talk about racecars and racing.”

Tom Alexander is the latest protégé to work in Smith’s garageandhopesonedaytoraceV8 Supercars. His chances are good if history is any judge.

Smith is hoping to put a V8 SuperTourers team together next year – he had hoped to enter one this year but couldn’t raise enough money – and sees more of a future in team management.

“I feel good when you can get a kid going good,” he says. “I don’t do it for money. If I was smart, I would sign up as their manager and head overseas with them but I get a thrill out of it when they win a race.”

Smith has rarely lost that winning feeling. He started winning at a young age and is still winning now.

He’s found the move into more modern race cars a challenge because of his advancing years and the stiffer suspension and smaller tyres that are features of classes such as the Toyota Racing Series which younger drivers are more able to cope with.

Put him in a Formula Atlantic or Formula 5000, and he’s still driving his 1975 Lola T332, and he’s consistently finishing in the top three if not at the front. He describes the ride as like getting into a “big, comfortable armchair”.

Smith mixed it with the likes of Jim Clark, Graham Hill and Chris Amon in their prime in the 1960s and ’70s, and many still wonder if he would have made it had he dedicated himself to chasing a Formula 1 drive.

“I have no doubt he would have been competitive,” McMurray says. “He should have gone overseas. He had the chance but declined for one reason or another.

“He could have made a very, very good living at that time – as long as he survived, of course, because it was a very dangerous time in motorsport. He gave up a career in international motorsport to stay here.”

Smith doesn’t regret staying in New Zealand but it occasionally nags at him.

“I probably should have gone to England and the States in the early days,” he says. “I probably could have got a [F1] drive. I can even remember seeing an old Autosport and them advertising for Formula 1 drivers. Well, they were killing them week by week, so I suppose they needed more.

“You make your life and do these things. You talk yourself into things and talk yourself out of it. Back in the ’70s, money wasn’t easy – $10,000 in those days was probably $500,000 today. I’m happy what I’ve done. I’ve raced in Asia and Australia and been successful in everything I’ve done.

“I raced in the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s, and that was racing. To me, Formula One is absolute bullshit today. The driver sits in the car and has so many controls and is told what to do. Michael Schumacher said that it was 20 per cent driver and 80 per cent car. In the old days, it was 80 per cent driver and 20 per cent car.”

Smith acknowledges he won’t win another New Zealand Grand Prix -he’s racedin46editionsand is keen to attain 50 starts-but he’s less worried about winning these days. Sometimes he’s more intent on which horse won the third at Ellerslie and many of his races have been delayed as he listens to a call.

Smith has the mangled chassis from a crash that broke his foot a couple of years ago hanging on his garage wall. It seems to act as both a trophy and a reminder but he has no fears of crashing because speed is a relative concept.

“I don’t feel fast. When you’re standing as a spectator, it looks pretty hairy and hard work, but when you are in the car, it’s totally different. You might think your mind has to be on everything but it’s when you relax that it all comes together. You have plenty of time. When you go down the straight in a powerful car, you almost have time to put a cigarette in your mouth and light it.”